Medicaid → Implementation → Retention

Retention

Retaining Medicaid members who have elected to participate in the National Diabetes Prevention Program (National DPP) lifestyle change program is an important program objective. In general, the longer individuals stay in the program, the better their outcomes. Retention also impacts the ability of a CDC-recognized organization to maintain CDC recognition and receive performance-based payments.

This page contains the following topics:

- Retention Improves Outcomes

- Retention Best Practices

- Retention Strategies in Practice

- Tailoring Retention Practices in Rural Areas

- Using Incentives and Program Supports

- Incentives and Program Supports in Practice

- Retention Statistics

Information about understanding and adapting to an individual’s readiness to participate in the program is available on the Recruitment and Referrals page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Retention Improves Outcomes

Research from CDC’s Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program (DPRP) 2017 dataset has shown the longer a person stays in the program, the better their outcomes. For example, CDC has found that there is a significant association between staying in the program past the first 16 weekly sessions and achieving the 5%+ weight loss. Participants that remain in the program for 17+ sessions (the second six months of the program) achieve weight loss at higher rates than those in the program for the first 16 sessions (the first six months of the program).

Additional retention and outcomes statistics from CDC analyses on the DPRP 2017 dataset are indicated below.

- Analyses on three weight loss distributions (low, medium, and high weight loss) found that individuals in all three groups, regardless of amount of weight loss, exhibited the same trend: those attending 17+ sessions and having an average of 150+ minutes of physical activity per week had increasingly higher percent weight loss among all race/ethnicity groups.

- For women with gestational diabetes mellitus, significant predictors of achieving 5% weight loss were meeting the 150 minutes of physical activity, attending ≥ 17 sessions, staying in the program for more than 183 days, and age 45–64 years.

- For every additional session attended and every 30 minutes of activity reported, participants lost 0.3% of body weight (p < 0.0001). See the ADA report here.

Medicaid Eligibility and Churn

Individuals move in and out of Medicaid eligibility frequently due to changing financial status or other reasons, often administrative in nature, that disqualify them for continuing coverage. This movement in and out of Medicaid coverage is often referred to as churn and can be a challenge for a year-long program like the National DPP lifestyle change program. Medicaid churn rates vary substantially by state and are dependent on the qualifying level of income for Medicaid eligibility. Beyond churn, there are many possible status changes that can occur for an individual that may impact their ability to participate in the program, including switching between Medicaid MCOs or health plans. For more information on churn and potential strategies states can consider to mitigate its effects, see the Reimbursement page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN) Impact Retention

Efforts to improve retention in the National DPP lifestyle change program often require broader approaches that address social, economic, and environmental factors that influence health. Social determinants of health (SDOH) are conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, pray, and age that affect a wide range of health, functioning, and quality of life outcomes. While everyone has socially determined factors of health, some populations and individuals may have health-related social needs (HRSN) stemming from these factors. While SDOH are broader social conditions, HRSN are more immediate individual or family needs impacted by those conditions. They include housing insecurity, food insecurity, or lack of reliable transportation that can lead to decreased health and a lower quality of life.

HRSN may serve as a barrier to both access and continued participation in the National DPP lifestyle change program. An increasing number of CDC-recognized organizations are structuring their programs so that some of these barriers to participation can be overcome, such as allowing for the provision of childcare vouchers and access to healthy food. For examples of how a CDC-recognized organization can address HRSN, see Addressing HRSN Through the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program page of the Coverage Toolkit.

For more information on SDOH and HRSN as they relate to the National DPP lifestyle change program, visit the suite of Health Equity and the National DPP pages on the Coverage Toolkit.

Retention Best Practices

Best Practices Guide

NACDD, Leavitt Partners, and the Minnesota Department of Health partnered to compile evidence- and experience-based best practices on recruitment, enrollment, and retention into a single Best Practices Guide. The guide is written for Lifestyle Coaches and program coordinators who serve low income, Medicaid-eligible participants. However, many of the principles discussed in the guide could be used by any partner working to increase recruitment, enrollment, and retention in the National DPP lifestyle change program and would apply to all eligible participants.

The Best Practices Guide contains the following nine retention related best practices. For each best practice, the guide includes the rationale behind the practice, tips for action, linked resources, and implementation examples from Lifestyle Coaches and program coordinators. In conjunction with the guide, the Minnesota Department of Health released a series of videos interviewing Lifestyle Coaches and program coordinators to emphasize the retention strategies detailed in the Best Practices Guide. The videos are linked in the best practices below.

-

1. Meet Unique Participant Needs

Enhance the National DPP lifestyle change program to meet the needs of specific participants. Enhancements may be tailored around the participants’ cultural community, gender, age, literacy level, disabilities, income level, and location (e.g., rural vs. urban). For example, address SDOH through the use of community health workers (CHWs) for culturally appropriate program delivery and utilize culturally relevant food and menu examples. Pages 27-29 of the Best Practices Guide provide a list of publications describing considerations and enhancements for various populations.

2. Use Low-Literacy Materials

Incorporate the use of additional low-literacy materials, such as visuals and materials written at a 6th grade level or below, to address SDOH-related educational barriers.

3. Address Barriers to Participation

Find creative solutions to address the common barriers that prevent participants from enrolling and/or continuing in the program, including SDOH-related barriers, such as addressing childcare or transportation concerns, and making it easier for participants to catch up on missed sessions.

4. Expand Flexibility through Online and Distance Learning

Increase access to the National DPP lifestyle change program by offering a combination of in-person, online, and/or distance learning delivery of the program.

5. Encourage Social Connections

Facilitate social connections between program participants during and outside of sessions such as through setting up a private social media group for the participants and organizing physical activities.

6. Offer Supplementary Experiences

Add variety and interest by offering unique supplementary experiences to participants, such as a grocery store tour, cooking demonstrations, or guest speakers. Address food insecurity by partnering with a local food shelter to provide healthy foods at each session.

7. Tailor Communications to Participants

Contact program participants frequently to encourage continued participation, and tailor the mode of communication to the preferences of the participants.

8. Use Incentives and Program Supports

Provide incentives and program supports related to healthy living. Additional information that is complementary to what is found in the Best Practices Guide can be found in the Using Incentives and Program Supports section below.

9. Provide Lifestyle Coach Training

Improve the participants’ experience by developing a team of highly skilled Lifestyle Coaches through continuing education.

Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project Retention Brief

NACDD, with funding from the Division of Diabetes Translation at CDC, led the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project with Maryland and Oregon to show how state Medicaid agencies and state health departments can collaborate to implement, deliver, and sustain coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program.

The strategies implemented by managed care organizations (MCOs), accountable care organizations (ACOs), and CDC-recognized organizations to increase participant retention during the Demonstration are summarized in the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project Retention Brief. The Demonstration Project concluded that the main reasons participants discontinued the program was due to time constraints, technology issues, family commitments, classes being held at inconvenient times, lack of reliable transportation, lack of reliable internet, and a perception of inability to achieve goals. These barriers may serve as focal points to improve National DPP lifestyle change program retention. The Demonstration Project also found that retention was improved when participants were referred by a health care provider, received program support tools, such as pedometers, scales, or athletic gear or clothing, and reported excellent or good health.

CDC Retention Resources

Retention Tip Sheet

CDC has developed a tip sheet that provides insights and lessons learned about improving participant retention, including how to establish participant buy-in, retention strategies for months 7-12, and how to build the capacity of Lifestyle Coaches to increase retention.

Personal Success Tool

CDC created the Personal Success Tool (PST) to help increase participant retention. It has interactive, web-based modules to encourage participants, reinforce information they have learned in class, and provide tailored support to meet their needs. The PST is based on behavior change theory and audience research, and has been tested by coaches and participants in nine National DPP lifestyle change programs. It includes motivational messages, testimonials, short games, quizzes, and participant pledges.

Who uses the PST?

The PST is designed for Lifestyle Coaches and National DPP lifestyle change program participants. Coaches use the PST to help participants stay engaged by sending related modules after each class. Participants can review the modules on a computer, smartphone, or tablet, and each activity only takes a few minutes to complete.

The PST is designed to follow the order of the PreventT2 curriculum, but can be used with any CDC-recognized National DPP lifestyle change program curriculum.

Lifestyle Coach Perspectives on the PST

- “Using the Personal Success Tool will help you stay motivated when you need extra encouragement.”

- “Completing the modules will reinforce what you learn in class, helping you master new ideas, and continue to be successful in the long term.”

- “…the PST is easy to use and only takes a few minutes to review during class.”

PST Resources for Lifestyle Coaches (Additional marketing resources, including Spanish language versions, are available on CDC’s PST page on the National DPP Customer Service Center)

- Lifestyle Coach’s Guide—an overview of the PST, including when and how to use it

- Quick Reference Guide—a printable worksheet to schedule when to send each module to program participants

- PST Talking Points—ideas on how to introduce the PST to program participants

- PST Participant Overview—a handout for program participants about the PST

Retention Strategies in Practice

The tabs below describe how various states and organizations have put retention strategies into practice.

Maryland

Maryland participated in the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project funded by CDC and managed by NACDD. A brief on the retention strategies implemented during that project can be found here.

A survey conducted with the participating Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) revealed some lessons learned regarding retention, including:

- Recruitment and retention success depended heavily on the participating MCOs’ traditional communication vehicle with its members. For example, while text messages worked well with one MCO that frequently communicated via text, texts from another MCO that did not traditionally communicate via text resulted in many confused members and lacked success.

- Class reminders from the MCO or CDC-recognized organization via phone and/or email both prior to the first class and before every class were helpful in recruiting and retaining participants.

To learn more about how the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project was implemented in Maryland and Maryland’s plan for ongoing sustainability of the program, visit the Maryland Medicaid Demonstration Project page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Minnesota

In 2016, the Minnesota Department of Health and the Minnesota Department of Human Services cited the following as critical success factors and/or best practices for engaging and retaining Medicaid members in the National DPP lifestyle change program. These factors are based on learnings from program implementation, key informational interviews, and participant focus groups:

- Providing services for participants, including transportation and childcare to eliminate barriers to participation

- Providing a healthy snack during the session

- Initiating reminder calls or letters and providing ongoing support to participants

- Building in extra time to support participants through sometimes challenging personal/familial circumstances

- Facilitating participant access to other support programs (e.g., food assistance, health insurance, housing support)

- Training community health workers and/or local community clinic staff to serve as Lifestyle Coaches (and ensuring that they can bill the hours necessary to deliver the program)

- Showing sensitivity to participants with low literacy (e.g., using photos instead of written text, using hands-on activities rather than reading from a script, etc.)

- Coordinating with the participants’ local primary care clinics

- Identifying, with the help of the clinics, a familiar and accessible meeting location for participants (e.g., not necessarily the YMCA, even if the Lifestyle Coach is from the YMCA)

- Hiring coaches from cultural backgrounds that match the cultural backgrounds of the participants (community health workers are a good option to fill this cultural need)

- Providing instruction in participants’ primary language (e.g., Somali, Hmong, Spanish)

- Translating some program materials (such as a food tracker) into the participants’ primary languages

To learn more about how the National DPP lifestyle change program has been implemented in Minnesota, see the Minnesota State Story of Medicaid Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Montana: Individuals with Disabilities

In 2012, Montana Medicaid started offering the National DPP lifestyle change program as a covered benefit to Medicaid enrollees with and without disabilities. Over the first two years, roughly one-third of program participants had a disability. Evaluations on the state’s program have indicated that, although individuals with disabilities tended to start with a higher BMI baseline and were less likely to achieve 5–7% weight loss, they could still successfully participate in the National DPP lifestyle change program. Some program adaptations may be necessary, however, to address their needs and to increase success.

A survey that gathered feedback from Lifestyle Coaches on the program revealed that some curriculum content was too complex for a subset of beneficiaries and that some participants found food journaling to be challenging. It further indicated that transportation is an obstacle to participation. Based on this and other survey feedback, the following recommendations were made:

- Engage family, case managers, and Medicaid transportation assistance services to help program participants with transportation

- Simplify curriculum content as needed

- Simplify self-monitoring tools as needed

- Provide individual support as needed

A program manager from the Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services also shared the following as valuable practices for implementing the program within the Medicaid population and for individuals with disabilities:

- Train Lifestyle Coaches on different types of disabilities (both physical and cognitive) and how those disabilities could impact how someone might learn, meet goals, and track eating. The Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services engaged the National Center on Health, Physical Activity and Disability (NCHPAD) to provide this training to Lifestyle Coaches.

- Train Lifestyle Coaches about issues and solutions relating to accessing health care and fitness centers (e.g., simple things someone could do to rearrange exercise equipment so that it could be more accessible to someone in a wheelchair).

- Enable Lifestyle Coaches to practice coaching and secure feedback from individuals that are knowledgeable about disabilities. For example, volunteers from the Montana Disability and Health Program at the University of Montana and Centers for Independent Living role-played as National DPP lifestyle change program participants, so that the coaches could practice supporting individuals with disabilities.

- Ensure that Lifestyle Coaches share budget-friendly food planning and physical activity information (e.g., talking about exercises that are free, or highlighting that frozen fruits and vegetables may be cheaper than fresh produce).

To learn more about how the National DPP lifestyle change program has been implemented in Montana, see the Montana State Story of Medicaid Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Oregon

Health Share of Oregon was one of the Coordinated Care Organizations that participated in the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project funded by CDC and managed by NACDD. A brief on the retention strategies implemented during that project can be found here. Some of the best practices and lessons that Health Share of Oregon learned from its experience were the following:

Lessons Learned:

- It is more difficult to motivate participants to continue to attend sessions when there are long gaps between them (i.e., monthly classes can be challenging to retain attendance)

- Incentives can be unsustainable if funded with grant money

- It is important to find the communication style that works best for the participants, whether it is text, phone call, or email

Best Practices:

- Barriers, such as childcare or transportation, should be addressed upfront

- Partnering with an early learning hub is one way to address childcare

- An accessible location, especially by public transit, is important

- Allowing family members or caretakers to also participate in the program promotes retention

- Resources should be modified for language and cultural relevance

- A mini evaluation at the end of each class ensures that methods and/or items promote success

- Communication can be used to keep participants engaged during the off-weeks

- Bringing in outside resources with additional information and tools can keep participants engaged

- Incentives, raffles, or challenges can provide additional motivation to participants

To learn more about how the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project was implemented in Oregon and Oregon’s plan for ongoing sustainability of the program, visit the Oregon Medicaid Demonstration Project page of the Coverage Toolkit.

YMCA

A senior director of evidence-based health interventions at the YMCA of the USA indicated that the following factors contributed to retaining participants:

- Ensuring that Lifestyle Coaches had strong facilitation skills, empathy, and can support an effective group dynamic

- Educating participants about the requirements of the program prior to the first session (including the program’s duration and the likely challenges of achieving behavior change)

Tailoring Retention Practices in Rural Areas

Various studies on diabetes education and prevention programs in rural areas have indicated the following factors as contributing to successful implementation:

- Providing participant transportation to classes when needed

- Hosting the program in a common, well-known location

- Developing positive relationships with and engaging providers, social workers, and other community partners

- Considering cultural sensitivities and differences between counties when recruiting and engaging participants

- Establishing support from community leaders

- Educating communities on the underlying SDOH factors

- Helping communities better understand their capacity, assets, and resources

- Gaining an understanding of local politics

- Offering the program via telehealth to increase access

The studies summarized above are found here: Appalachia, Montana, Montana telehealth, Federal Office of Rural Health Policy (FORHP).

In addition, NACDD collected the following information from state and local health department representatives from Montana, Colorado, North Dakota, and Ohio regarding challenges facing rural populations and opportunities to mitigate those challenges.

Access

Challenge

- Lack of Lifestyle Coaches or CDC- recognized organizations

- Limited broadband internet access in some rural areas

Opportunity

- Online delivery options, where internet is available

- Program delivery in-person and via telehealth technology to remote sites (for an example of how telehealth delivery can be implemented, see the Montana State Story of Medicaid Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit)

- Encouraging the following to deliver the program: Cooperative Extension System through land grant universities; places where people already gather such as community and senior centers, churches, and libraries; and hospital systems that have identified obesity as a priority through community health assessments

Travel Time

Challenge

- Travel distances—both for coaches and participants—can be further in rural areas

Opportunity

- Encouraging carpooling, which also enhances opportunities for support

- Use “buy one, get one free” registration deals to engage spouses or friends

- Providing gas cards as incentives

- Have several Lifestyle Coaches trained in each organization to share the travel burden

Participants Moving

Challenge

- Participants may move to a different location throughout the year

Opportunity

- Allow participants to join a class at other locations so they can complete the yearlong program

Participation

Challenge

- Finding a marketing strategy for the rural population

Opportunity

- Local radio

- Local free newspapers available in grocery stores

- Use digital strategies. See the CDC’s resource on Strategies that Work: Using Digital Strategies to Reach Rural Populations here*.

- Use word-of-mouth marketing. See the CDC’s resource on Strategies that Work: Using Word-of-Mouth Marketing to Reach Rural Populations here*.

Marketing

Challenge

- Finding a marketing strategy for the rural population

Opportunity

- Local radio

- Local free newspapers available in grocery stores

- Use digital strategies. See the CDC’s resource on Strategies that Work: Using Digital Strategies to Reach Rural Populations here*.

- Use word-of-mouth marketing. See the CDC’s resource on Strategies that Work: Using Word-of-Mouth Marketing to Reach Rural Populations here*.

Lifestyle Coach Support

Challenge

- Since Lifestyle Coaches may be spread out, it may be difficult to support them

Opportunity

- Monthly support calls and annual face-to-face meetings to offer refresher training, support, resources, and best practices

Recruitment and Referrals

Challenge

- Because of the diffused population, it may be difficult to identify potential participants

Opportunity

- Support from rural health/hospital systems is critical as it may be the only medical care in the area

- Screening and testing through employers is also key

- Having a neutral party organize referrals (e.g., the Cooperative Extension) allows providers to have one number for referrals to programs

- Gaining buy-in from local health care providers and hospitals

Using Incentives and Program Supports

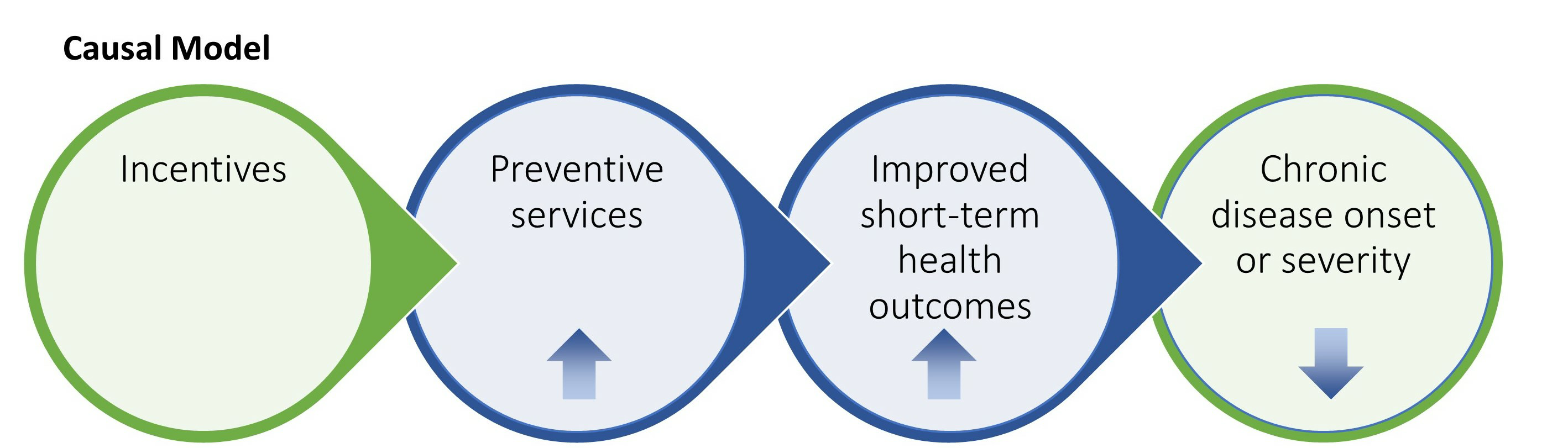

Some CDC-recognized organizations and their partners use incentives and program supports to enhance participant enrollment and retention. In this context, program supports are items, services, and activities that:

- Reinforce information in the curriculum. Examples include measuring cups and cooking demonstrations.

- Remove barriers to participation. Examples include transportation vouchers, weight scales, mobile devices, and prepaid phone minutes or data.

- Address social determinants of health. Examples include access to healthy foods and referrals to community resources.

- Promote social support and connectedness. Examples include one-on-one meetings with the Lifestyle Coach and social media groups.

In general, programs have shown to have higher attendance rates when they include incentives or program supports.

Source: MIPCD Final Evaluation Report – Figure E-2

There are many characteristics of a good incentive program that are important to consider. It will be important to determine:

- Who will receive the incentive

- What type of incentive will be given (e.g., cash, vouchers, gifts, etc.)

- What target or goals will need to be achieved to receive the incentive

- When participants will receive the incentive (e.g., immediately following achievement of the target or goal, on a fixed schedule, etc.)

- What the value of the incentive will be

- Whether the incentive is guaranteed (e.g., when using a lottery method, the incentive is not guaranteed)

- Whether the incentive employs a positive (carrot) approach for engaging in a healthy behavior or a negative (stick) approach where a loss is achieved for not engaging in a healthy behavior or achieving an outcome.

- Whether the incentive is aligned with program goals and provides additional support for individuals to achieve the desired outcomes

The sessions during the last six months of the program emphasize maintaining a healthy lifestyle that was learned in the first six months of classes. Participation in these classes provide continued support and motivation to the program individuals seeking to retain a healthy lifestyle. When developing incentives, steps should be taken to develop a model that encourages participants to maintain participation throughout the second six months of the program, in addition to the first six months.

For an example of how to select the characteristics of a good incentive program, see the MIPCD Grant States example below.

The CDC’s Division of Diabetes Translation has released a number of resources on using incentives and program supports with National DPP lifestyle change program participants. These include:

- Using Program Supports to Enhance the National DPP Webinar: CDC highlights the key efforts to scale the National DPP in areas that are underserved, discusses the partners in that effort, and shares approaches from organizations that used various types of program supports to help reinforce information in the program curriculum, remove barriers to participation, address social determinants of health, and promote social support.

- Emerging Practices - Guide for Using Incentives to Enroll and Retain Participants: This guide provides information about incentives for organizations that are interested in using them. It describes different types of incentives and the level of evidence to support them. It also provides information about factors to consider when deciding whether to use incentives.

- Keys to Success - Using Program Supports for Retention: This tip sheet provides lessons learned and insights from organizations that used program supports to retain participants in their lifestyle change programs.

- Incentives Can Improve Diabetes Health Measures: This infographic Illustrates the high-level findings from the study, providing examples of effective types of incentives for program participants and outlining how organizations can best design program incentives for improved health results.

Note: When covering the National DPP in Medicaid, consideration will need to be given to the type of incentives and program supports that can be offered. Generally, federal Medicaid matching funds cannot be used to pay for program incentives (unless the state has received approval through an 1115 or other waiver). As such, state or grant funds may be needed to pay for program supports or incentives. Medicaid MCOs could also pay for program incentives out of their administrative funds.

Additionally, organizations receiving funding from CDC or through a CDC cooperative agreement should consult the program guidance before planning to use incentives. The use of CDC funds to purchase certain items may be restricted or have certain guidelines that organizations should adhere to.

Incentives and Program Supports in Practice

The examples below describe how various organizations have approached offering incentives and program supports in their National DPP lifestyle change programs.

CDC: Lifestyle Modification Programs

In 2022, CDC published a research study about the use of incentives in lifestyle modification programs (like the National DPP lifestyle change program and diabetes self-management education and support services) and how they can benefit participants. The manuscript details how individuals in lifestyle modification programs who received an incentive improved their body weight, body mass index, and blood pressure more than participants who did not receive an incentive.

Maryland

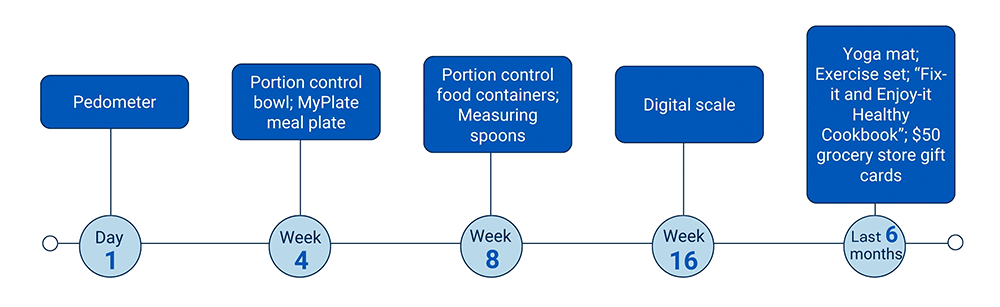

One Maryland MCO that participated in the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project provided various program supports according to the schedule below.

To learn more about how the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project was implemented in Maryland and Maryland’s plan for ongoing sustainability of the program, visit the Maryland Medicaid Demonstration Project page of the Coverage Toolkit.

MIPCD Grant States

Ten states received Medicaid Incentives for the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (MIPCD) grants. Four of the ten states—Minnesota, Montana, Nevada, and New York—used a subset of the grant dollars to fund incentives specifically for the National DPP lifestyle change program. A summary of key findings from the evaluations is provided below.

The study found that participants receiving incentives had significantly higher attendance (attended 1‒2 more National DPP lifestyle change classes) than control groups without incentives. However, beneficiaries indicated that while incentives served as a hook to get them enrolled, they were not the driver behind continued participation. Reaching goals, starting to feel better, and establishing a relationship with a coach who cares about them and acknowledges their successes were what kept them engaged.

The study also found that the type of incentive used is very important and that consideration must be given to its value and appropriateness. For example, while incentives increased attendance, they did not necessarily increase usage of other services evaluated through the grant, such as meetings with a health coach or doctor or gym visits. In the preliminary evaluation, several programs indicated that they had provided program participants with gym memberships, but later found that the participants weren’t using them because some people did not know how to use a gym, were overweight and uncomfortable wearing exercise clothes in the gym, or were from a culture that did not approve of co-ed gyms.

The timing and delivery of incentives are also crucial. Incentives should be given as soon as a person meets their goal—the clearer the relationship is between the incentive and the goal, the better the results. In states where this relationship was delayed—where a person had to wait until the next time they came into the class to receive the incentive or wait until it arrived in the mail—it resulted in people being frustrated or not realizing that the incentive was tied to reaching a goal.

The study of the incentive design proved inconclusive. When states tested different approaches to offering incentives—such as tying the incentive to activities, outcomes, or both—there was no clear pattern to suggest that one incentive design was more successful than another in improving health or reducing claims-based expenditures and utilization.

The MIPCD final evaluation report can be accessed here.

Montana

Montana conducted a study testing the effectiveness of using financial incentives for participation in its Medicaid National DPP lifestyle change program. Participants in the incentive cohort were given incremental financial incentives, up to a maximum of $320, for attendance, behavior change, and weight loss goal achievement. The median incentive amount earned was $110 per participant during the 3-year study.

While the study found that the incentive cohort attended significantly more sessions, reported greater physical activity, and self-monitored fat more frequently compared to the non-incentive cohort, there was no significant difference between the two cohorts in attaining greater than 5% or 7% weight loss.

To learn more about how the National DPP lifestyle change program has been implemented in Montana, see the Montana State Story of Medicaid Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit.

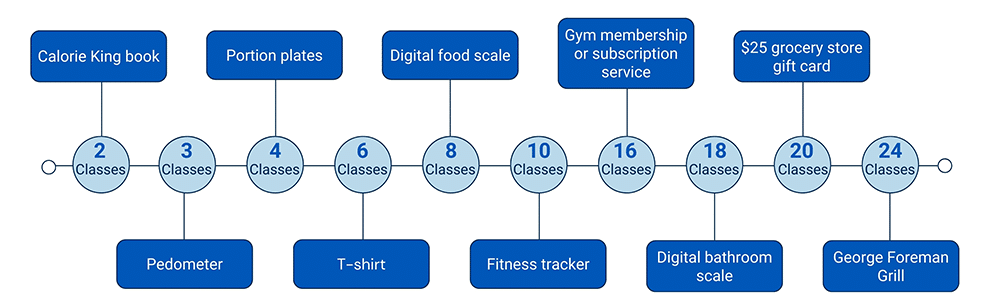

North Carolina: Minority Diabetes Prevention Program

North Carolina received state funds through their Office of Minority Health and Health Disparities to establish North Carolina’s Minority Diabetes Prevention Program, which focuses on increasing minority access to and participation in National DPP lifestyle change programs. It provided grant funding to partners across the state to market and administer the program. Some of the partners used incentives and program supports to promote healthy habits according to the schedule below. Program retention statistics are included in the Statistics on Enrollment and Retention subsection below.

Oregon

Health Share of Oregon, one of the Coordinated Care Organizations that participated in the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project, shared that one of its best practices relating to program supports includes making sure they are related to the material and that it promotes healthy living. It also suggested, as a consideration, to partner with other organizations to provide deals, prizes, or other incentives when there is no funding available.

To learn more about how the Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Demonstration Project was implemented in Oregon and the plan for ongoing sustainability of the program, visit the Oregon Medicaid Demonstration Project page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Six National Organizations

In 2012, CDC funded six national organizations through a five-year cooperative agreement to scale and sustain multistate networks of CDC-recognized organizations to deliver the National DPP lifestyle change program. A study based on this effort found that most of the CDC-recognized organizations offered the following three types of program supports and incentives to retain participants in the National DPP lifestyle change program. The incentives were program-funded and were not supported by federal funding.

- Non-monetary Program Supports

- Program supports included gym memberships, pedometers, food-measuring devices, or cookbooks

- Used by 118 of the reporting CDC-recognized organizations (78.7%)

- Monetary Incentives

- Incentives included coupons or gift cards (less than $25 value)

- Used by 32 of the reporting CDC-recognized organizations (21.3%)

- Removal of Barriers of Access

- Program supports included childcare or transportation passes

- Used by 29 of the reporting CDC-recognized organizations (19.3%)

Only the non-monetary incentives were found to significantly impact attendance. When non-monetary incentives were used participants attended an average of 1.8 more sessions and participated in the program an average of 27.8 more days.

Another retention tool utilized by the CDC-recognized organizations was cultural adaptation (e.g., using cultural images, and incorporating cultural dietary restrictions and preferences). When cultural adaption was used participants attended an average of 1.4 more sessions and participated in the program an average of 29.5 more days.

Retention Statistics

The following examples illustrate state and partner experiences with retention numbers in their implementation of the National DPP lifestyle change program.

Denver Health

Denver Health, a Colorado-based safety net health system, attempted to recruit 4,495 individuals that it identified as being eligible for the National DPP Lifestyle Change program using medical record data. A total of 782 of these individuals, or 17.4%, attended at least one session. Further, approximately 1 in 10 at-risk individuals would enroll (i.e., verbally commit to participating in a session) when contacted by a Lifestyle Coach, whereas nearly 1 in 2 individuals would enroll if referred by their provider.

Of the 617 participants who completed the yearlong program, 238 (38.6%) attended nine or more sessions. Approximately 50% of the participants were Medicaid beneficiaries and 80% were low income.

Denver Health: Latinos

Denver Health conducted a study to determine how results differ between Latino and non-Hispanic white participants enrolled in the National DPP lifestyle change program. It found that Latinos were approximately half as likely to attend the sessions and were also less likely to achieve 5% weight loss when compared to the non-Hispanic white participants. Discovering and resolving barriers to participation among Latinos may be a key step in improving attendance and reducing their risk reduction outcomes. The study can be found here.

North Carolina: Minority Diabetes Prevention Program

Of the individuals who enrolled in North Carolina’s Minority Diabetes Prevention Program, 50% of participants completed at least 4 classes, 33% completed at least 8 classes, and 25% completed at least 9 classes.

A 2023 Report by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services on the Minority Diabetes Prevention Program is available here.

YMCA

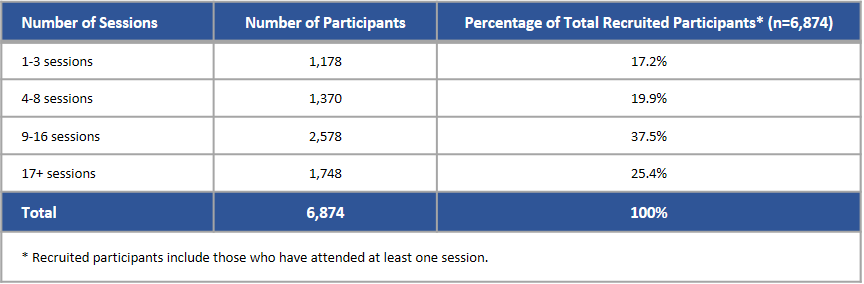

The YMCA of the USA implemented the National DPP lifestyle change program with Medicare beneficiaries, through support from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s Health Care Innovation Awards. The YMCA of the USA DPP 2015 Annual Report found at the end of the eleventh quarter (March 2015), that of the 6,874 Medicare beneficiaries who attended at least one session, 82.9% attended four or more sessions (see table below). For additional data reports from this project, see CMS’ Health Care Innovation Awards page.

Table included in the CMMI Y-DPP model test evaluation report; reformatted for this site.