Medicaid → Medicaid Coverage → The Role of the State Legislature in Medicaid Coverage

The Role of the State Legislature in Medicaid Coverage

NOTE: State agency staff should consult with their internal legislative counsel, governmental affairs, agency director, and/or supervisor as needed about how to engage in their state’s legislative process.

Understanding the role of the state legislature in establishing Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program can be important for state agencies and private sector stakeholders alike. This page contains the following content regarding how legislation has been used to facilitate Medicaid coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program:

- What is the Role of the Legislature in Establishing Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program?

- How Stakeholders May Engage with the Legislature

- National DPP State Legislation Examples

- National DPP Administrative Rule Change Examples

What is the Role of the State Legislature in Establishing Medicaid Coverage for the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program?

Making the National DPP Lifestyle Change Program a Covered Benefit in Medicaid

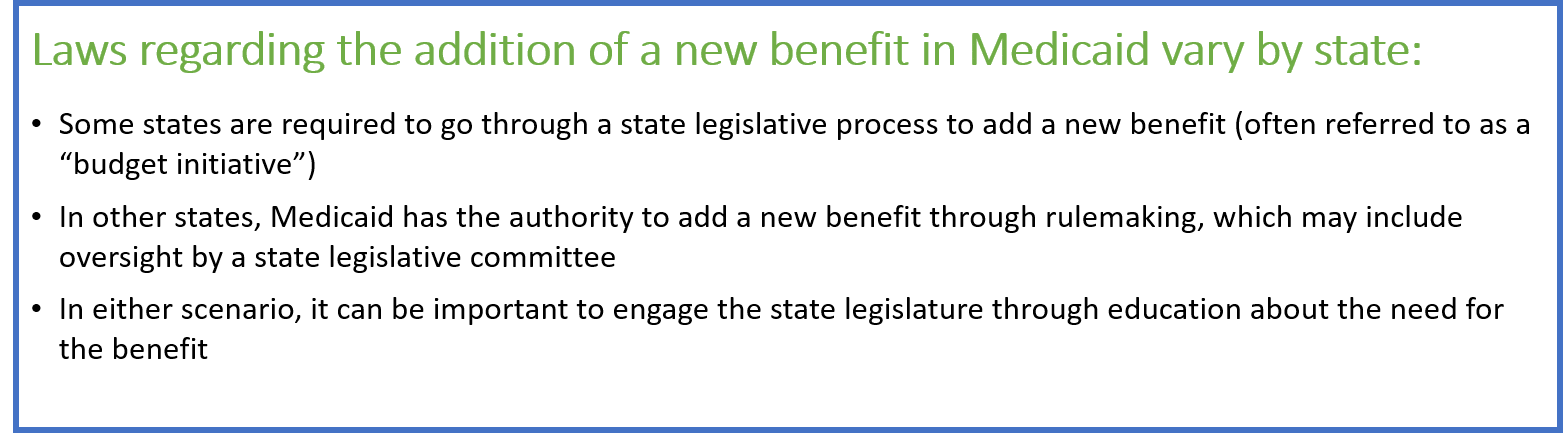

If a state has made the decision to add the National DPP lifestyle change program as a covered benefit in Medicaid, some Medicaid agencies are required to include the program in their state’s Medicaid statute before covering it. This would involve the submission of a bill to the legislature (see the Engaging in the Legislative Process section below). In other states, Medicaid agencies have the authority to establish and determine the details of the benefit through rulemaking, and a change to the state’s Medicaid statute is not required to cover the program.

Once Medicaid is covering the National DPP lifestyle change program, the state will determine the best way to secure federal Medicaid matching funds. This can be accomplished through the Medicaid State Plan, a section 1115 demonstration waiver, or other mechanisms (see the Engaging MCOs to Attain Coverage page).

Why Work with the Legislature

Regardless of whether going through the legislative process is required, Medicaid agencies and their partners would likely benefit from engaging the legislature when establishing Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program, particularly because the new benefit will likely require an increase in funding. Involving and educating the state legislature can increase their buy-in for funding, help inform the broader community about the program, help ensure the long-term viability of the program, and encourage cross-agency cooperation in implementing the program. Statutory changes may also increase the urgency of implementation by including deadlines for when Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program must begin.

If states are not ready to cover the National DPP lifestyle change program in Medicaid, agencies and advocates can seek legislation that supports the convening of task forces, workgroups, committees, councils, or advisory groups to study the impact of type 2 diabetes in the state and possible solutions. This type of legislation could include language about the composition of the group, required deliverables, and timelines. For examples, see Kentucky and Pennsylvania’s legislation in the National DPP State Legislation Examples section below. Special legislative assignments such as these often have the requirement to report to the legislative body prior to the start of new legislative sessions and may mandate that state agencies work together. In the case of Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program, this interagency collaboration can be especially important.

Medicaid Expansion

Another consideration when exploring legislative involvement is whether a state has expanded Medicaid eligibility under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). These states tend to cover more adults who may be eligible for the National DPP lifestyle change program, and many have seen their rates of diabetes increase as their covered population has expanded.

The demographics of the covered populations under “traditional” Medicaid programs (e.g., those states that have not undergone expansion) primarily include pregnant women, children under the age of five years, physically and mentally disabled persons who qualify for social security, persons who have substance abuse (addiction) issues, and adults in long-term care. In states that have expanded Medicaid eligibility, the federal government will cover 90% of the cost of direct services provided to newly eligible childless adults up to 138% of the federal poverty level (FPL). These states may be more likely to consider coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program, as it may be more relevant and financially impactful for their covered population.

How Stakeholders May Engage with the Legislature

NOTE: State agency staff should consult with their internal legislative counsel, governmental affairs, agency director, and/or supervisor as needed about how to engage in their state’s legislative process.

Types of Stakeholders

If seeking a statutory change to enact a benefit, it may be helpful to educate and mobilize stakeholders (including state coalitions or advisory councils, as available), identify target lawmakers from whom to seek support, and work with a legislative research group before legislation is drafted. Since state employees typically cannot directly lobby for the passage of a bill, stakeholders can be critical partners. It may be especially important to outreach to and educate key legislators such as members of the health care committee, the Senate president, the Speaker of the House, and the state Governor’s office.

Lobbyists can be important stakeholders in researching, creating, and advocating for the passage of specific bills. Other partners in this effort could include representatives from the American Diabetes Association (ADA), diabetes care and education specialists, community health organizations, and CDC-recognized organizations. Mobilizing a state coalition of partners who are willing and motivated to participate can be particularly powerful. For example, in California, Public Health Advocates (PHA) and a coalition of partners played a critical role in helping get legislation passed for Medicaid coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program. A description of their role can be found on the California’s State Story of Medicaid Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit. State agencies can be prepared to support advocates through information preparation and fiscal notes.

Educating Stakeholders

Succinct, state-specific policy briefs with state data, recommendations for legislative action, and executive summaries can be an effective way to introduce legislators and other stakeholders to an issue. These briefs should describe the problem and why it needs to be addressed, identify the solution, summarize how much it will cost (and/or save), and what impact it will have on the state population. Having additional materials on hand, such as a slide deck or an in-depth report, is a good idea for stakeholders who are interested in learning more. Seeking statutory changes for Medicaid benefits is considered a budget initiative for Medicaid and state agency staff should be prepared with fiscal impact statements. For information and templates to educate and mobilize stakeholders to work with policymakers, visit the Medicaid Case for Coverage page of the Coverage Toolkit.

In addition, when considering new legislation or policy, the chairs and staff of key legislative committees often reach out to the relevant staff and interest groups to get their input. This input may be sought as part of committee hearings that occur in the months preceding the start of the legislative session. Key agency officials are often invited to present background research to these committees and to answer questions about how the proposed changes will affect operations, expenses, and outcomes. Other stakeholders (those listed above as well as university professors, public health experts, private and public sector interests, professional groups, patient advocates, etc.) may present data and testimony regarding the benefits or drawbacks of any proposed changes.

In some states, Medicaid agency or public health agency employees are not be permitted to propose legislation or take a position on legislation, and agency approval may be necessary to engage in the education of legislators. In addition, bills that are proposed during the legislative session require agency input. This input can be delivered through fiscal and program impact statements. These are additional opportunities to share evidence about the National DPP.

Engaging in the Legislative Process

Each state has a unique process for enacting bills, and stakeholders should ensure they understand the rules applicable in their state. A description of the legislative process used in each state can be found here.

Depending on a state’s legislative process, stakeholders may be able to support bills related to the National DPP lifestyle change program in the following ways. Some of the listed activities may not be applicable to all stakeholders.

- Sharing relevant state data. Stakeholders may be able to ignite public and legislator interest in type 2 diabetes prevention by sharing the right data (for an example of where this occurred, see California’s State Story of Medicaid Coverage). Some key state-specific statistics include the prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes; the prevalence of type 2 diabetes risk factors, such as obesity; direct medical costs associated with type 2 diabetes; indirect medical costs associated with type 2 diabetes, such as lost productivity and disability; and the costs and benefits of the National DPP lifestyle change program. For more information on relevant data, see the Case for Coverage for Medicaid page of the Coverage Toolkit.

- Performing pre-session work to inform the legislature or the appropriate committees on the proposed benefit. This can also be an opportunity to identify co-sponsors. The pre-session work often includes convening the state diabetes coalition or advisory council to strategize the best way to share relevant data with the legislature and holding meetings in key legislative districts for advocates, citizens, and policymakers to discuss the proposed benefit.

- Identifying state legislators interested in sponsoring the appropriate bill in the legislature (ideally committee chairs and/or majority party leaders, or a health-related caucus or committee).

- Working with legislative staff and other interested groups to draft a bill that meets the goals of the interested party and bill sponsor/co-sponsors, and addresses any budgeting requirements.

- Participating in committee hearings with public comment. Some states require a bill to pass multiple committees, whereas other states only assign a bill to one committee. Agencies and other stakeholders may testify at these hearings, or provide advanced materials to the legislature and legislative staff, including positions of support, opposition, information, and fiscal impacts. In some states committee hearings may occur prior to the legislative session. State legislatures often require the bill to be read several times. Stakeholders can track the progress of bill readings to remain current with the bill’s progression.

- Repeating the bill committee and floor process in the other house. In most states, if a bill is passed in the House of Representatives, the bill must also be passed by the Senate, and vice versa (i.e., “cross-over”). During this process, the bill is again open for amendments and continued advocacy and communication about the bill will likely be necessary for passage. In some states, both bodies will have committee hearings and floor readings on a bill simultaneously, following which conference committees are used to reconcile differences in the resulting bills.

Timing Considerations

Stakeholders interested in engaging with the legislature should be aware of their state’s legislative session dates. States vary in their legislature type (full-time, part-time, or hybrid), membership size, term length for legislators, and session calendar. Most part-time legislatures convene from January through March or even mid-May for a prescribed number of days that may not be contiguous.

For states that apply managed care within Medicaid, the timing of managed care organizations (MCO) contracts is yet another consideration. Contracts between the state and the Medicaid MCOs are generally renegotiated every few years and in some states it may be difficult to begin a new benefit between contracts. Keeping these timeframes in mind as they align with the legislative process may be helpful. For more information, visit the State MCO Contracts and Contract Amendments page of the Coverage Toolkit.

Follow-Up Administrative Processes

When a new statute is passed authorizing Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program, a state Medicaid agency will typically be given authority to create administrative rules that specify how the benefit will be operationalized. Administrative rules are agency regulations that elaborate on the details or requirements of a law. In the context of Medicaid coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program, administrative rules may include application requirements for new provider types, billing and coding procedures such as ICD-10 use requirements, required provider type credentials and accreditation, and data and reporting procedures. For example, the Montana administrative rules related to the National DPP lifestyle change program can be found here (rules 37.86.5401 to 37.86.5404). There typically will be a written comment period to receive public input on the administrative rule and some states may hold public hearings on rule changes. Agencies work to address all the public comments and ensure stakeholders’ comments are formally responded to.

Once the Medicaid agency has published the administrative rules, the state legislature may again become involved before the rule becomes final. Often, legislatures may review the rules proposed by Medicaid (and other) agencies to ensure they comply with the statute and legislative intent. Forty-one states have some type of authority to review administrative rules, and some have veto authority. In some states, legislative standing committees are responsible for reviewing the work of the state agencies, or the state legislature may have created special committees or staff agencies to evaluate state agency operations. External interested parties may choose to maintain contact with legislators in case the statute or administrative rules need modifications in the future.

As noted earlier, once a state is covering the National DPP lifestyle change program in Medicaid, the state will determine the best way to secure federal Medicaid matching funds. This can be accomplished through the Medicaid State Plan, a section 1115 demonstration waiver, or other mechanisms (see the Engaging MCOs to Attain Coverage page).

National DPP State Legislation Examples

The language used to make any statutory change will vary by state. Below are some examples of legislative language that states have used to move towards Medicaid coverage or state employee coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program.

California

Senate Bill (SB) 97 enacted July 10, 2017, and Assembly Bill (AB) 1810 enacted June 27, 2018

On July 10, 2017, California passed Senate Bill 97, which required the State Department of Health Care Services (i.e., Medicaid) to establish the National DPP lifestyle change program within the Medi-Cal fee-for-service and managed care delivery systems, authorized a Medi-Cal provider to refer the program to beneficiaries who are eligible, and required lifestyle coaches to use a specific curriculum. This legislation permitted the following individuals to deliver and be reimbursed for the program as lifestyle coaches from an enrolled DDP provider:

- Physicians,

- Nonphysician practitioners (like physician assistants or nurse practitioners), and

- Unlicensed personnel who have been trained to teach CDC’s Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program’s (DPRP) approved curriculum

About a year later, AB (Assembly Bill) 1810 changed California’s eligibility requirements for a beneficiary to participate in the National DPP lifestyle change program to align with CDC’s DPRP requirements. The final statute resulting from SB (Senate Bill) 97 and AB 1810 is as follows:

-

(1) Emphasizes self-monitoring, self-efficacy, and problem-solving.

-

(2) Provides for coach feedback.

-

(3) Includes participant materials to support program goals.

-

(4) Requires participant weigh-ins to track and achieve program goals.

“4149.9. (a) It is the intent of the Legislature that the department pursue policies and programs to assist Medi-Cal beneficiaries in preventing or delaying the onset of type 2 diabetes.

(b) (1) The department shall establish the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) within the Medi-Cal fee-for-service and managed care delivery systems.

(2) A Medi-Cal managed care plan shall make the DPP available to enrolled beneficiaries in accordance with this article.

(c) In implementing the DPP, the department shall require that Medi-Cal providers offering DPP services comply with guidelines issued by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and obtain CDC recognition in connection with the National Diabetes Prevention Program.

(d) The DPP shall be an evidence-based, lifestyle change program designed to prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes among individuals with prediabetes.

(e) The DPP shall be made available to Medi-Cal beneficiaries no sooner than July 1, 2018.

(f) A Medi-Cal provider may identify and recommend participation in the DPP to a beneficiary who meets the eligibility requirements of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Diabetes Prevention Recognition Program.

(g) In implementing the DPP, the department shall require Medi-Cal providers offering DPP services to use a CDC-approved lifestyle change curriculum that does all of the following:

(h) DPP services shall be provided by peer coaches, who promote realistic lifestyle changes, emphasize weight loss through healthy eating and physical activity, and implement the DPP curriculum. A trained peer coach may be a physician, a nonphysician practitioner, or an unlicensed person who has been trained to deliver the required curriculum content and possesses the skills, knowledge, and qualities specified in the National Diabetes Prevention Program guidelines.

(i) A beneficiary who participates in the DPP shall be allowed to participate in 22 peer coaching sessions over a period of at least one year. Thereafter, the department shall provide a participating beneficiary who achieves and maintains a required minimum weight loss of 5 percent from the first core session, in accordance with CDC standards, with less intensive, ongoing maintenance sessions to help the beneficiary continue healthy behaviors.

(j) (1) The department shall develop payment methodologies, or adjust existing methodologies, for reimbursing DPP services and activities in the Medi-Cal fee-for-service delivery system, not to exceed 80 percent of the federal Medicare Program reimbursement for comparable service, billing, and diagnosis codes under the federal Medicare Program.

(2) For purposes of reimbursement under the Medi-Cal fee-for-service delivery system, an unlicensed peer coach shall have an arrangement with an enrolled Medi-Cal provider for purposes of reimbursement for rendered DPP services.

(k) This article shall be implemented only to the extent that the department obtains federal financial participation to the extent permitted by federal law, and obtains any necessary federal approvals.

(l) For the purposes of implementing this article, the department may enter into exclusive or nonexclusive contracts on a bid or negotiated basis, including contracts for the purpose of obtaining subject matter expertise or other technical assistance…”

Bolding added for emphasis.Kentucky

Kentucky wrote two resolutions to help increase coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program in the state.

Senate Concurrent Resolution (SCR) 6, introduced in Senate January 8, 2019

Kentucky’s first resolution, SCR 6, was a concurrent resolution that urged private health insurance providers to study the impacts of implementing the National DPP lifestyle change program, and implement similar programs if their research found cost savings or improved client health outcomes. This resolution included some of the following language:

“The General Assembly respectfully urges all private health insurance providers doing business in Kentucky to study the potential impacts of implementing programs similar to the Kentucky Employees’ Health Plan’s Diabetes Value Benefit plan and Diabetes Prevention Program. Impacts studied should include but not be limited to the estimated cost of such programs, the potential health benefits of such programs, and any possible financial savings that may be achieved by such programs. The General Assembly further urges such companies to implement programs similar to KEHP’s Diabetes Value Benefit plan and Diabetes Prevention Program if the results of their studies indicate a likelihood of cost savings or improved client health outcomes.”

Senate Joint Resolution (SJR) 7, enacted May 19, 2019

The second resolution, SJR 7, was a joint resolution directing the Department of Medicaid Services to study the impacts of implementing programs similar to the National DPP lifestyle change program for Medicaid beneficiaries. The impacts included cost, health benefits, and potential savings. The resolution also outlined that the Department of Medicaid Services will submit a report of their findings. The resolution passed 36-0 and 66-0 in the House and Senate respectively.

“Section 1. The Department for Medicaid Services shall conduct a study of the potential impacts of implementing programs similar to the Kentucky Employees’ Health Plan’s Diabetes Value Benefit plan and Diabetes Prevention Program for Medicaid beneficiaries in the Commonwealth. Impacts studied shall include but not be limited to the estimated cost of such programs, the health benefits such programs may afford Medicaid beneficiaries, and any potential financial savings that may be achieved by such programs.

Section 2. The Department for Medicaid Services shall submit a written report of its findings from the study required by Section 1 of this Resolution to the Legislative Research Commission’s Interim Joint Committee on Health and Welfare and Family Services by November 1, 2019…”

Massachusetts

H 2209/HD 660, in process as of January 21, 2020

Massachusetts’ H 2209/HD 660 plans to provide the National DPP lifestyle change program to state employees. The bill has bipartisan support. As of April 22, 2020, the bill’s language is as follows:

“Chapter 32A of the General Laws, as appearing in the 2014 Official 2 Edition, is hereby amended by inserting after section 17O the following section:

Section 17P. The commission shall provide to any active or retired employee of the commonwealth who is insured under the group insurance commission and is identified as someone with prediabetes those items and services furnished under a diabetes prevention program recognized as a National Diabetes Prevention Program as established by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.”

New Jersey

Assembly Bill 2993, enacted July 21, 2017

This bill allowed for Medicaid coverage of three diabetes-related programs, including the National DPP lifestyle change program. The legislation also directed “the Commissioner of Human Services to apply for State Plan Amendments or waivers necessary to implement the provisions of the bill and to secure federal financial participation for State Medicaid expenditures under the federal Medicaid program.” The language used in the bill is as follows:

“b. Subject to the limitations imposed by federal law, by this act, and by the rules and regulations promulgated pursuant thereto, the medical assistance program may be expanded to include authorized services within each of the following classifications:…

(22) Upon referral by a physician, advanced practice nurse, or physician assistant of a person diagnosed with diabetes, gestational diabetes, or pre-diabetes:

(a) Expenses for diabetes self-management education or training to ensure that a person with diabetes, gestational diabetes, or pre-diabetes can optimize metabolic control, prevent and manage complications, and maximize quality of life. Diabetes self-management education shall be provided by:

(i) a licensed, registered, or certified health care professional who is certified by the National Certification Board of Diabetes Educators as a Certified Diabetes Educator, or certified by the American Association of Diabetes Educators with a Board Certified-Advanced Diabetes Management credential, including, but not limited to: a physician, an advanced practice or registered nurse, a physician assistant, a pharmacist, a chiropractor, or a dietitian registered by a nationally-recognized professional association of dietitians; or

(ii) an entity meeting the National Standards for Diabetes Self-Management Education and Support, as evidenced by a recognition by the American Diabetes Association or accreditation by the American Association of Diabetes Educators;

(b) Expenses for medical nutrition therapy as an effective component of the person’s overall treatment plan upon a: diagnosis of diabetes, gestational diabetes, or pre-diabetes; change in the beneficiary’s medical condition, treatment, or diagnosis; or determination of a physician, advanced practice nurse, or physician assistant that reeducation or refresher education is necessary. Medical nutrition therapy shall be provided by a dietitian registered by a nationally-recognized professional association of dietitians familiar with the components of diabetes medical nutrition therapy;

(c) For a person diagnosed with pre-diabetes, items and services furnished under a diabetes prevention program that meets the standards of the National Diabetes Prevention Program, as established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and

(d) Expenses for any supplies and equipment recommended or prescribed by a physician, advanced practice nurse, or physician assistant for the management and treatment of diabetes, gestational diabetes, or pre-diabetes, including, but not limited to: equipment and supplies for self-management of blood glucose; insulin pens; insulin pumps and related supplies; and other insulin delivery devices.”

New York

S 1507C/A 2007C, enacted April 12, 2019

New York State’s legislation, S 1507/A2007, was a budget bill and includes an amendment to the social services law that includes the National DPP lifestyle change program within the definition of “standard coverage” for medical assistance for needy persons. Amending the social services law also authorized CDC-recognized organizations to enroll in New York State Medicaid and receive Medicaid reimbursement. The language in the budget bill is as follows:

“Subdivision 2 of section 365-a of the social services law is amended by adding a new paragraph (ff) to read as follows: (ff) evidence-based prevention and support services recognized by the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC), provided by a community-based organization, and designed to prevent individuals at risk of developing diabetes from developing Type 2 diabetes…

§ 4. This act shall take effect July 1, 2019.”

With this change, New York Consolidated Laws, Social Services Law – SOS § 365-a now reads as follows:

“The amount, nature and manner of providing medical assistance for needy persons shall be determined by the public welfare official with the advice of a physician and in accordance with the local medical plan, this title, and the regulations of the department…

2. “Standard coverage” shall mean payment of part or all of the cost of medically necessary medical, dental and remedial care, services and supplies, as authorized in this title or the regulations of the department, which are necessary to prevent, diagnose, correct or cure conditions in the person that cause acute suffering, endanger life, result in illness or infirmity, interfere with such person’s capacity for normal activity, or threaten some significant handicap and which are furnished an eligible person in accordance with this title and the regulations of the department. Such care, services, and supplies shall include the following medical care, services, and supplies, together with such medical care, services, and supplies provided for in subdivisions three, four and five of this section, and such medical care, services, and supplies as are authorized in the regulations of the department:…

ff) evidence-based prevention and support services recognized by the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC), provided by a community-based organization, and designed to prevent individuals at risk of developing diabetes from developing Type 2 diabetes.”

Bolding added for emphasis.To learn more about New York State’s pathway to Medicaid coverage of the National DPP lifestyle change program, visit the New York State Story of Medicaid Coverage page.

Pennsylvania

House Resolution 936, adopted Sept. 24, 2014

This resolution directed the Joint State Government Commission, in collaboration with certain other State departments and agencies, to develop a report for the House of Representatives every two years on reducing the incidence of diabetes and improving diabetes care in Pennsylvania. The language of the resolution is as follows:

“…RESOLVED, That the House of Representatives direct the Joint State Government Commission to submit a report on diabetes that identifies goals and benchmarks and includes plans to reduce the incidence of diabetes, improve diabetes care and control complications associated with diabetes; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission develop the report on diabetes in collaboration with all of the following:

(1) The Department of Health.

(2) The Department of Public Welfare.

(3) The Department of Education.

(4) The State Employees’ Retirement System.

(5) The Health Care Containment Council.

(6) Any additional State departments or agencies the commission deems appropriate to develop, research and prepare the report;

and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission assess the financial impact and reach diabetes has on the residents of this Commonwealth and the State departments and agencies collaborating on the report, and that the assessment include all of the following:

(1) The number of individuals with diabetes impacted or covered by the State department or agency.

(2) The number of individuals with diabetes and family members impacted by prevention and diabetes control programs implemented by the State department or agency.

(3) The financial toll or impact diabetes and its complications placed on State department or agency programs.

(4) The financial toll or impact diabetes and its complications placed on the State department or agency programs in comparison to other chronic diseases and conditions;

and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission conduct an assessment of the benefits of implemented programs and activities aimed at controlling diabetes and preventing the disease, and that the assessment include the amount and source for any funding from the Federal Government and the General Assembly for programs and activities aimed at reaching those with diabetes; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission provide a description of the level of coordination existing between State departments and agencies on activities, programmatic activities and messaging on managing, treating or preventing all forms of diabetes and its complications; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission provide detailed plans and recommendations for the control and prevention of diabetes for consideration by the General Assembly, and that the plans and recommendations do all of the following:

(1) Identify proposed action steps to reduce the impact of diabetes, pre-diabetes and related diabetes complications.

(2) Identify expected outcomes of the action steps proposed in the following biennium.

(3) Establish benchmarks for controlling and preventing relevant forms of diabetes; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission develop a detailed budget blueprint identifying needs, costs and resources required to implement the plans and recommendations of each department or agency, and that the blueprint include a budget range for all options presented in the recommendations identified by each department or agency for consideration by the General Assembly; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission provide the initial report on the estimated number of individuals with diabetes, pre-diabetes, or related diabetes who are served by each department or agency and any additional information the commission deems appropriate to the General Assembly by March 1, 2015; and be it further

RESOLVED, That the Joint State Government Commission submit a comprehensive report on the items listed in this resolution to the Diabetes Caucus of the House of Representatives and the Human Services Committee and the Health Committee of the House of Representatives by September 15, 2015, and by September 15 of each odd-numbered year thereafter following the release of the initial report.“ Bolding added for emphasis.

The fourth biennial report of the Joint State Government Commission on diabetes in Pennsylvania was released in September of 2019.

National DPP Administrative Rule Change Examples

Below are some examples of administrative rule language that states have used to move towards Medicaid coverage for the National DPP lifestyle change program.

Idaho

Idaho Administrative Procedure Act (IDAPA) 16.03.09 (page 78-79) effective July 1, 2023.

In July 2023, the state Medicaid agency used rulemaking authority to temporarily add the National DPP lifestyle change program as a covered benefit under Medicaid. This administrative rule was accompanied by a MedicAide Newsletter (page 5-6) released in July 2023 from Idaho Department of Health & Welfare (Idaho Medicaid) that outlines additional details of the benefit.

Select language used in the administrative rule is as follows:

-

01. Participants with Diabetes. Are eligible for a Diabetes Management Program when:

-

a. A recent diagnosis of diabetes within ninety (90) days of enrollment with no history of prior diabetes education; or

-

b. Uncontrolled diabetes manifested by two (2) or more fasting blood sugar of greater than one hundred forty milligrams per decaliter (140 mg/dL), hemoglobin A1c greater than eight percent (8%), or random blood sugar greater than one hundred eighty milligrams per decaliter (180 mg/dL), in addition to the manifestations; or

-

c. Recent manifestations from poor diabetes control including neuropathy, retinopathy, recurrent hypoglycemia, repeated infections, or nonhealing wounds.

-

02. Participants with Pre-Diabetes. Are eligible for the National Diabetes Prevention Program when they meet the program’s guidance.” Bolding added for emphasis.

-

01. Diabetes Management Program. The education and training services are provided through a diabetes management program recognized as meeting the program standards of the American Diabetes Association or Association of Diabetes Care and Education Specialists by a certified diabetic educator. (7-1-23)T

-

02. The National Diabetes Prevention Program. The provider meets the requirements for the program.” Bolding added for emphasis.

“641. DIABETES EDUCATION AND TRAINING SERVICES: PARTICIPANT ELIGIBILITY.

The medical necessity for diabetes education and training are evidenced by the following:

“644. DIABETES EDUCATION AND TRAINING SERVICES: PROVIDER QUALIFICATIONS AND DUTIES

Outpatient diabetes education and training services will be covered under one (1) of the following conditions: (7-1-23)T IDAHO ADMINISTRATIVE CODE IDAPA 16.03.09 Department of Health & Welfare Medicaid Basic Plan Benefits Section 645 Page 79

Ohio

Ohio Administrative Code Rule 5160-8-53 effective January 1, 2022.

On December 17, 2021, the Ohio legislature approved a change to the administrative code, establishing Medicaid payment for the National DPP lifestyle change program effective January 1, 2022. As a result of the administrative rule change, all MCOs in the state are required to cover the National DPP lifestyle change program for their members. This administrative rule was accompanied by a Medicaid Transmittal Letter that outlines additional details of the benefit. To learn more, please visit Ohio’s State Story of Medicaid Coverage.

Select language used in the administrative rule is as follows

-

(1) Providers.

-

(a) Rendering providers. The following providers may render or supervise an NDPP service:

-

(i) A physician;

-

(ii) A physician assistant;

-

(iii) An advanced practice registered nurse;

-

-

(b) Billing (“pay-to”) providers. The following providers may receive Medicaid payment for submitting a claim for an NDPP service on behalf of a rendering provider:

-

(i) A physician;

-

(ii) A physician assistant;

-

(iii) An advanced practice registered nurse;

-

(iv) A professional medical group;

-

(v) A federally qualified health center;

-

(vi) A rural health clinic; or

-

(vii) An ambulatory health care clinic;

-

-

-

(2) Coverage.

-

(a) Payment for an NDPP service can be made when all of the following criteria are met:

-

(i) The individual is eighteen years or older;

-

(ii) The individual is overweight;

-

(iii) The individual is not currently pregnant; and

-

(iv) The individual does not have a diagnosis of type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

-

(v) At least one of the following criteria is met:

-

(a) The individual has been diagnosed with prediabetes;

-

(b) The individual has a history of gestational diabetes; or

-

(c) The individual has had a high-risk result on a prediabetes test.”

-

-

-

“(C) NDPP.